Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was the first black president of the

Republic of South Africa, serving from 1994 to 1999

Republic of South Africa, serving from 1994 to 1999

On July 18, 1918, Mandela was born along the Mbashe River in the village of Mvezo, in the Umtata district. AllAfrica.com and the BBC both report that Mandela was "born Rolihlahla Dalibhunga." Mandela explains in his 1994 autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, that he was given the English name "Nelson" by his teacher Miss Mdingane on his first day at school, which he explains was a common practice within white South African institutions, where whites were unable or unwilling to pronounce African names.

In Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela writes that "[a]part from life, a strong constitution, and an abiding connection to the Thembu royal house, the only thing my father bestowed upon me at birth was a name, Rolihlahla. In Xhosa, Rolihlahla literally means 'pulling the branch of a tree,' but its colloquial meaning more accurately would be 'troublemaker.'"

Mandela's father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, was chief of Mvezo in the Transkeiean territories, and from the African indigenous Thembu royal family line. His mother was Nosekeni Fanny, the third of his father's four wives. Mandela was one of thirteen children and had three older brothers.

The Education of Nelson Mandela

In 1930, when Mandela was nine years old, his father died. He was adopted by the paramount chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo. Under the Regent Jongintaba's guardianship, Mandela attended Wesleyan Mission School, where he was trained for leadership. He also studied at Clarkebury Boarding Institute and Wesleyan College. He also studied at Fort Hare University before he and Oliver Tambo were expelled in 1940 after boycotting against university policies. In a turn of history, the University of Hare would later establish the Nelson R. Mandela School of Law.

Mandela began his law studies at the University of Witwatersrand, but would earn his law degree in 1942 from the University of South Africa. Mandela's political activism made his legal studies a challenge; he initially failed the exams required for his LLB law degree in 1948. This was the same year the apartheid promoting National Party won its political victory. Along with Sisulu, Tambo, and others, Mandela organized the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) in Johannesburg.

By 1952, Mandela opened his law office, teaming up with Oliver Tambo to create the first black legal practice in South Africa. Mandela became the ANCYL's deputy national president. Here, he challenged institutional apartheid and fought for civil rights through land redistribution, trade union rights, and free and compulsory education for all children. The same year, the apartheid government banned Mandela's attendance at any political meetings or from holding an office within the ANC under the Suppression of Communism Act. In response, Mandela and Tambo initiated the M-plan (M for Mandela), which broke the ANC down into cells that could operate underground if necessary.

The Treason Trial and the Start of an Armed Struggle

On December 5, 1956, in response to the adoption of the Freedom Charter at the Congress of the People, Nelson Mandela and Chief Albert Luthuli, then ANC President, were among the 156 people arrested and charged with high treason for their political activism. Punishment for high treason was death. Those arrested included most of the leadership of the ANC, Southern African Indian Congress, Coloured People's Congress, Congress of Democrats, and the South African Congress of Trade Unions, known collectively as the Congress Alliance. Eventually acquitted, during the treason trial Nelson Mandela met and eventually married his second wife Nomzamo Winnie Madikizela (aka Winnie Mandela, Winnie Madikizela Mandea and Nomzamo Winifred Madikizela). She would be his champion during his 27 years of incarceration as a political prisoner.

Photo of Nelson Mandela with Winnie Mandela

South African Apartheid and the Sharpeville Massacre

While Mandela was formerly committed to non-violent protest, he began to believe that armed struggle was the only way to achieve change. He co-founded Umkhonto we Sizwe, also known as MK, an offshoot of the ANC dedicated to an armed struggle, including sabotage and guerrilla war tactics to end apartheid. By 1959, however, the ANC lost much of its militant support when the Africanists broke away to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

On March 21, 1960, 69 black Africans were killed and about 180 were injured when the South African police opened fire on demonstrators at Sharpeville. This transformed the ANC's strategy from a nonviolent movement using civil unrest techniques such as boycott, strike, civil disobedience and non-cooperation, to that of an armed struggle using guerrilla warfare against the apartheid regime.

As a brief history of European settlement, the Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias was among the first Europeans to reach the region in 1487. The two major groups were the Xhosa and Zulu peoples at the time of European contact in Southern Africa. By 1652, Dutchman Jan van Riebeeck established a settlement at the Cape of Good Hope at Cape Town on behalf of the Dutch East India Company. Dutch is the primary origin of the Afrikaan language, with an estimated 90 to 95 percent of Afrikaans vocabulary being of Dutch origin.

South Africa commemorates the 50th Anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre

Nelson Mandela: From Prison to Presidency

In 1964, Mandela was arrested again, this time on a charge of sabotage. This time, however, he was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was incarcerated on Robben Island, near Cape Town, as prisoner 46664 for 18 of his 27 years in prison. Mandela imprisonment became a symbol of black oppression and a world-wide symbol of the resistance to racism. It sparked Pan Africanist responses from the Americas through support of organizations like TransAfrica under the efforts of the African American lawyer Randall Robinson. Mandela gained world-wide support, even from Europe. He was allowed to study for a Bachelor of Laws through a University of London correspondence program.

Mandela may have become the most revered prisoner in modern history. He would indeed be the trouble-maker, using his life to help dismantle apartheid to form a new multiracial democracy. In 1990, Nelson Mandela was released from prison under then leadership of his country's president Frederik Willem de Klerk. By July 1991, he was elected president of the ANC. In 1993, Mandela and de Klerk were both awarded Nobel Peace Prizes.

Photo of Nelson Mandela and Frederik de Klerk at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 1992

On May 10, 1994, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was elected the first black South African president as a result of its first multiracial elections. The same year he married Evelyn Mase, Walter Sisulu's cousin. He served as president until 1999 before retiring from active politics. He maintained a busy schedule of fund-raising for his Mandela Foundation, which aims to build schools and medical clinics in South Africa�s rural regions. In 2001, he was diagnosed and treated for prostate cancer. June 2004, at age 85, he announced his formal retirement from public life.

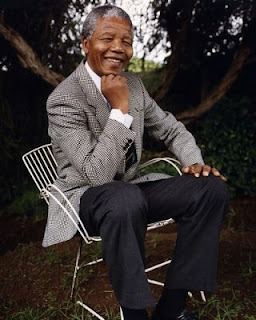

Photo of Nelson Mandela in his native South Africa